On Certainty

The convoluted story of an Ice Hockey championship, Elmyra Duff, clarity, and a ghost haunting the rigid machinery.

It is 1957. For the first time in history, the Ice Hockey World Championships are being held in the Soviet Union. This event of great international prestige is being hosted in the Central Lenin Stadium in Moscow. A great many preparations have gone into ensuring a successful tournament. Every detail has been meticulously planned for the tournament to run like clockwork. However, the political circumstances are grim. The Cold War is gripping the world. A popular uprising in Hungary has been violently crushed, and the Soviet Army is now occupying the country. In protest, the United States, Canada, West Germany, Norway, Italy, and Switzerland are boycotting the games. For the Soviet Union, this is an embarrassment, but also a blessing in disguise. With these countries absent, the Soviet Union is by far the strongest contender in the championship and heavily favored to win. And indeed, it outperforms all other teams to face underdog Sweden in the finals. By the third and last period of the game, the Soviet Union leads Sweden by two points and is headed for victory. But, as you might have guessed, this is the beloved story of the underdog. The Swedish players muster all their skill, creativity, and wit to score two spectacular goals and end up tied with the Soviets. Based on the results of previous games, this puts the Swedes ahead in the final point count. The game is over. Sweden is World Champion. Hooray! What happens next is instructive. At the gold medal ceremony, the organizers are stumped. For all their meticulous planning, the Soviets never considered the possibility that Sweden might win. They failed to prepare the Swedish national anthem and are unable to play it. To avoid embarrassment, it is swiftly agreed that the Swedish team will sing their national anthem themselves. The ceremony is held with great pomp and the trophy respectfully handed over to the Swedish team. All dignitaries rise and stand to attention. Chief among them Soviet General and Minister of Defence Marshall Zhukov, a member of Nikita Khrushchev’s inner circle. As he stands and performs a military salute, the Swedish team starts singing:

Helan går

Sjung hopp faderallan lallan lej

Helan går

Sjung hopp faderallan lej

Och den som inte helan tar

Han heller inte halvan får

If, like me, you do not speak Swedish, here is a loose translation: ‘Bottoms up. Sing “hup fol-de-rol la la la la.” Bottoms up. Sing “hup fol-de-rol la la.” He who doesn’t drink the first shall never, ever quench his thirst.’ Of course, this is not Sweden’s national anthem. That would be ‘Du gamla, du fria’, but in 1957, the Swedish ice hockey team did not know all the words to that song. So, instead they chose to prank the Russians and sing the popular drinking song, Helan går.

So what can we learn from this story? First, bring warm undies when traveling to Moscow in the winter, but also, for Pete’s sake, DO NOT invade Hungary! All jest aside, this story makes an important point about the confidence we place in our predictions. And it is my segway to a predictive activity that is key to the functioning of human society. Forecasting. Forecasting is a powerful thinking tool because it extends our agency into the future. It is a thinking tool that creates foresight. Foresight yields insight, and insight can be used to formulate a strategy. This strategy can be put into action, leading to a position of competitive advantage. Or, at the very least, it can prevent you from having the whole world watch you stand to attention, while the Swedish national team pranks you with a drinking song.

Forecasting

Foresight has led to a competitive advantage since Homo sapiens first appeared 300 thousand years ago. However, it became a vital necessity for survival in the early agrarian societies when harvests depended on the timing of meteorological events and seasonal changes. It is no coincidence that the first high civilizations of Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Babylon were organized around kings that claimed to be direct descendants from sun gods that controlled the skies. Of course, forecasting techniques have evolved significantly since then. Whereas in ancient Babylon, forecasts were based on omens identified in the livers of sacrificial animals, today we wield sophisticated quantitative methods to analyze time series on data from the weather, ocean tides, or the Dow Jones Industrial Average. Whereas in Han Dynasty China two thousand years ago, imperial astronomers determined a person’s fate based on the position of the planets, sun, moon, and comets, today we have experts making forecasts about interest rates, presidential elections, nuclear disarmament, and most gripping of all, celebrity divorce proceedings. Networks of satellites coupled with meteorological sensor arrays are able to forecast atmospheric events with great accuracy. The Voyager 1 space probe was launched on September 5th, 1977 and has traveled on an accurately forecast trajectory past Jupiter, Saturn, its moon Titan, and into interstellar space. It is over 22 billion kilometers away from Earth and still predictably transmits data to us via the Deep Space Network.

Clearly, humanity has come a long way since reading the entrails of antelopes to divine our fate. Our ability to forecast events has consistently improved through the technological and intellectual advances made by engineers, academics, and scientists, continuously driving progress to ever more dizzying heights. This narrative is beautiful and seductive. Unfortunately, it is also wrong. Or, at least, it paints only a partial picture that gives a misleading impression. It implies that progress is linear, and that the more we know the better we forecast. Of course, neither is true. As Philip Tetlock famously pointed out in his book Expert Political Judgment,¹ experts are often no better at making predictions than dart-throwing chimpanzees. And like those primates, they are rarely held accountable. Tetlock was quick to point out that this statement should not be misconstrued to mean all expert prediction is worthless. He went on to prove this point by organizing the Good Judgment Project, assembling a motley group of volunteers from diverse backgrounds to forecast world events based on publicly available information. These people were asked to answer questions about geopolitics, finance, entertainment, and sports. The results indicate that the top performers in this group outperformed intelligence operatives with access to classified information by about 30%.² In his follow-up book Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction, Tetlock identifies three traits common among superforecasters. He says that in philosophic outlook they tend to be cautious, humble, and non-deterministic. In my view these traits are all indicators of the individual’s relationship with uncertainty. Let’s look at each one in turn.

Caution: Tetlock describes good forecasts as being in perpetual beta, meaning that they are made by carefully weighing different points of view, and then thoughtfully updated as new information becomes available. This also means being able to change one’s mind when a situation changes. It requires active open-mindedness, a view that beliefs are hypotheses to be tested, not treasures to be protected. A concept we have explored in chapter one in the form of island and treasure metaphors. Superforecasters avoid overconfidence based on beliefs or biases. They do not fall for the illusion of control and realize that nothing is certain. They are better forecasters because they are aware that all around us, uncertainty is ever present.

Humility: This feature is widely misunderstood to be associated with weakness, insecurity, inadequacy, and self-doubt. Nothing could be further from the truth. Intellectual humility is the understanding that the world around us is infinitely complex. A style of thinking that recognizes irreducible uncertainty all around. It views reality as dissonant, messy, and convoluted. An environment in which human judgment is frequently flawed, and mistakes will be made. Humility requires the courage to admit our limitations. More than just an attitude, it is an antidote to dogma. It makes our thinking more flexible and dynamic. It protects us from sunk-cost fallacies, the doubling down on previous commitments in the face of increasingly negative outcomes. When we find ourselves in a hole, it enables us to stop digging and start climbing.

Non-determinism: The understanding that the world is infinitely complex leads to the conclusion that outcomes are not pre-determined. If every single action is affected by a myriad influences, then what happened could just as well have happened differently. In Tetlock’s words: “the world we live in is but one that emerged, quasi-randomly, from a vast population of once-possible worlds. The past did not have to unfold as it did, the present did not have to be what it is, and the future is wide open. History is a virtually infinite array of possibilities.” There is a poetic quality in this statement. We tend to think of the future as uncertain. But the same applies to the past and present. Nothing is certain. Hindsight makes history look like a linear progression of events that happened the way they had to. But nothing is further from the truth. Every moment is steeped in uncertainty, pregnant with alternate worlds waiting to be born — until the arrow of time casts one into existence.

To summarize, caution protects a good forecaster from overconfidence by recognizing uncertainty. Humility acknowledges the limitations of our judgement under uncertainty. Non-determinism extends uncertainty along the arrow of time — into the phenomenon of cause and effect. For these reasons, I submit that the acknowledgment, understanding, and domestication of uncertainty should be a prerequisite for anyone making forecasts. Or decisions. The alternative is as unpalatable, as it is well documented in history: Eminent men stroking their chins. However, the act of opening up to uncertainty, and the embrace of the world as complex, messy, and unpredictable runs counter to a highly sought-after quality among people making decisions. Confidence. Across human history, rulers, leaders, advisors, experts; they have all used the same parlor-trick, the same slight-of-hand to legitimize authority and privilege. This method consists in wielding a magic power. The power to ordain the future. Or in other words, the power to impose certainty. Of course, it is just a trick. Confidence is the signal emitted by this illusory power. Yet, we crave it. Like a moth to a flame, we are drawn to those who wield it. This serves the magician by legitimizing dominance, but also serves the audience. Herein lies the dirty secret of all authority. Even when it is imposed by force, the subjects tacitly crave and embrace the certainty provided, in the hope that it will translate into control and predictability. This uncertainty reduction is our desperate attempt to frieze time and space. To cast the world into stone. Our futile attempt to make it HOLD STILL. Then, and only then, can we make sense of the world using our augmented thinking tools. Only then, can we draft a model representation of the world and extract meaning from existence. Only once it stops moving. Inert. Lifeless.

From this perspective, humanity shares a striking resemblance with Elmyra Duff. Elmyra is a cartoon character from the Warner Bros. television series Tiny Toon Adventures. She is a cute, redheaded girl who lives in a nice, suburban home and attends Acme Looniversity. She serves as the school nurse and loves animals above all. In her pleated skirt, white socks, and black shoes, she stalks the neighborhood looking for animals. When she encounters one, she picks it up and expresses her love by hugging it. Tight. Tighter. And tighter. Until life starts to drain out of the creature. Of course, this is not love. It is an obsession coupled with a pathological disregard for life. This is reflected in the many abandoned pet toys, doghouses, and kitty baskets strewn across Elmyra’s ghostly back yard. Elmyra wears a light blue bow in her hair. If you look close, you see that it is held together in the middle by a gerbil’s skull. I am haunted by the image of humanity as Elmyra. So obsessed with certainty, that we drain life from all that which we encounter. I am terrified by our craving for control and prediction, profit and growth. Our back yard strewn with decaying toys and abandoned houses. I am horrified by the ceremonial headgear we wear in this ritual of destruction. A crown adorned with the symbol of our lasting legacy on this planet: the skull.

Clarity

As we traverse this gloomy vestibule of hell, listening to the muffled screams of uncommitted souls, I am not quite ready to follow the advice inscribed overhead: “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.” ³ We may be addicted to certainty. But addictions can be overcome. The first step is to acknowledge it and demand change. The addict needs to visualize the positive future effects of this change, while remaining painfully aware of the negative externalities of the addiction. It is here we find reason for hope. Even in the hard-nosed world of corporate leadership, men and women in Saville Row suits are waking up to the realization that future seas will be rough. A leading light in this arena is Robert Johansen, former president and CEO of the Institute for the Future (IFTF). In his book Leaders Make the Future: Ten New Leadership Skills for an Uncertain World, he says:

“What will be new in the years ahead is the scale and intensity of the VUCA World. Having spent forty years forecasting, I believe that the future world will be more volatile, more uncertain, more complex, and more ambiguous than we have ever experienced as a planet before. [ ] One of my jobs as a forecaster is to help people learn to be comfortable being uncomfortable — but certainly not passively comfortable.” ⁴

He goes on to make an interesting claim coming from a professional forecaster. The claim that nobody can predict the future — especially in a VUCA world. For Johansen, forecasting is about provocation, not prediction. It matters not that forecasts are right, or even that you agree with them. The best forecasts are “those that make you squirm in your chair.” They are meant to reveal uncertainty and make you uncomfortable, in the hope that this provocation will reveal new insights and make you take action. Most importantly, Johansen recognizes the fallacy of certainty as an acute problem in leadership. His solution is to replace the need for certainty with what he calls clarity. Where certainty is the feeling of absolute knowing, clarity includes the awareness of the unknown — the acknowledgment that reality is messy and full of contradictions. Where clarity is curious, certainty is dogmatic. Where clarity is expressed in narratives, certainty is expressed in rules. Where clarity is resilient, certainty is brittle.

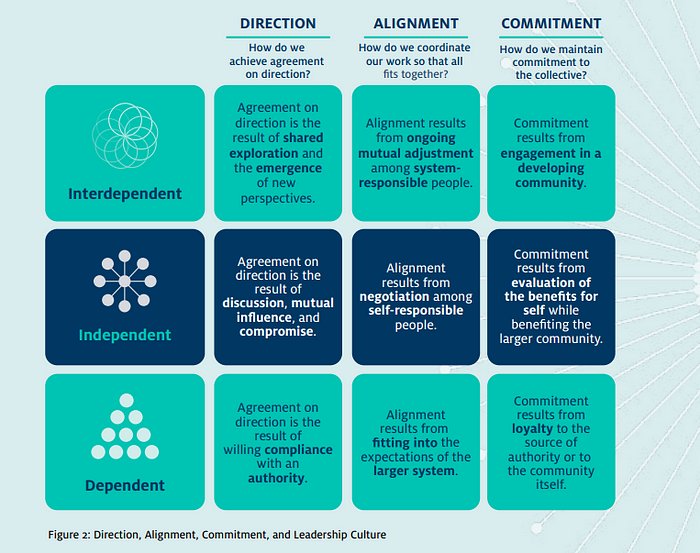

The Centre for Creative Leadership (CCL) identified that clarity ought to be a cornerstone of leadership culture. That is because this culture often overrides an organization’s vision, goals, and objectives. It defines three types of leadership styles: Dependent, Independent, and Interdependent. Leadership is seen by the CCL as social process of people working together to achieve results. Therefore the three styles differ significantly in how they achieve direction (goal setting), alignment (coordination), and commitment (taking responsibility). The Dependent culture sets the direction through a direct, top-down mandate of authority. Alignment with this direction is ensured by enforcing hierarchy, and commitment is achieved by demanding loyalty. The Independent leadership style achieves direction through group discussion and compromise. Alignment is negotiated and responsibility shared, whereas commitment is maintained by incentives and benefits. Lastly, an Interdependent leadership sets direction by collective exploration of a shared vision. It seeks internal alignment by appealing to the mutual sense of responsibility of its members, and achieves committed community engagement.

The difference could not be more stark. How these cultures establish power structures and resolve conflict is immediately apparent, but they also differ in a more subtle way. That is, in how they deal with uncertainty. In the Dependent leadership style, uncertainty is to be avoided at all cost. For this top-down hierarchy to function, automated processes and compliance with authority must be stable and predictable. Long-term forecasts guide sluggish cycles of adaptation and reluctant change. In such a system, risk is bad, and uncertainty is corrosive. A ghost haunting the rigid machinery. In contrast, the Independent style is more devolved from central control. Decision-makers are empowered to take calculated risks where benefits are perceived. Efficient feedback loops are there to catch errors early in the process. Adaptation is encouraged and some uncertainty tolerated. But there are limits. The experts making decisions cannot be perceived to fail, lest their position of privilege be questioned. The added degrees of freedom come at a cost. They are paid for in the currency of insulation. Each devolved center of power seeks short-term predictability. Externally, to project success. Internally, to maintain control. Innovation is possible, but slow and hampered by reluctantly placing uncertainty in risk-managed sandboxes. Now to the last of the three CCL leadership styles, Interdependent. This style actively promotes exploration of the space of possibilities by an engaged community. It continuously innovates and seeks the emergence of new perspectives. Uncertainty is not only tolerated, it is actively embraced. It is the fertile ground for the creativity needed to achieve a competitive advantage.

This is further expanded on in Braided Organizations: Designing Augmented Human-Centric Processes to Enhance Performance and Innovation. In this book, Michel Zarka and his co-authors describe how organizations are pioneering digitally-enabled collaboration to harness the power of an distributed network of contributors without the need for top-down hierarchies and traditional management structures. The advantages, according to the authors are: “improved coordination among individuals and groups performing interdependent tasks; increased organizational agility; enhanced knowledge-processing as experts contribute more directly to the most important technical and strategic decisions; and greater motivation, as people team together to leverage their capabilities to innovate and accelerate performance.” ⁵

I fervently hope that a pattern is emerging by now. Out of the fog of risk and ambiguity, a path emerges. To see it, one must cast aside the obsession with prediction and control. This is not to put a negative spin on certainty. Society needs stability to function. Nothing wrong with that. But it also requires creativity and innovation to adapt and survive. That is why, in an ever more rapidly changing world, I advocate for more acceptance of uncertainty. I beg for tolerance of ambiguity, petition for active open-mindedness, and plead for curiosity, caution, and clarity. Then, and only then, can we hope to thrive in our hypercomplex world instead of hugging it to death. Or, in the immortal words of one of my personal heroes, Timothy Morton:

“Automation means prolonging the past for the sake of what is now called ‘certainty’. Predictable profit. Predictable growth. Predictable planet death. Good to know that will happen in advance. Creativity means uncertainty. It means you might not know whether your plan is right. It means knowing that your plan can never be perfectly right. It will always have a flaw. Your economics, your ecology. It will never map earth perfectly. Never one to one. How wonderful is that. Acknowledging finitude. To exist is to be flawed. To be broken. To be wounded” ⁶

FOOTNOTES:

1 Tetlock, P.E. (2006–08–20). Expert political judgment: How good is it? How can we know?. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978–0–691–12871–9.

2 Spiegel, Alix. “So You Think You’re Smarter Than A CIA Agent”. NPR.org. Retrieved 2014–08–18.

3 Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy. Canto III

4 Tetlock, Philip E., and Dan Gardner. Superforecasting : the art and science of prediction. New York: Crown Publishers, 2015. Print.

5 ZARKA, MICHEL, ELENA KOCHANOVSKAYA, and William A. Pasmore. BRAIDED ORGANIZATIONS : designing augmented human-centric processes to enhance performance and … innovation. Place of publication not identified: INFORMATION AGE PUB, 2019. Print.

6 Lecture to the UF School of Art + Art History